By: Kaleab K. Haile

This blog argues that more empirical investigations on the effect of aggregate economic shocks on household investments in boy and girl child human capital development in the SSA context is needed. This data can help to prioritise disaster responses that mitigate gender biases and, in turn, alleviate gender inequality in human capital development in SSA.

Aggregate Shocks and Household Investment in Human Capital

Aggregate economic shocks induced by environmental, health, political, and financial crises disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable households. This is especially true in developing countries because they lack the institutional and policy support mechanisms that buffer vulnerable populations against the effects of these shocks. For an uninsured and liquidity-constrained household, negative income shocks have repercussions for household behaviour and attitudes towards investing in child human capital, because the sudden loss of financial stability raises the cost of health care and education relative to household income. The parents’ ability and willingness to bear the direct and opportunity costs of health inputs (i.e., allocating resources to health care services) and schooling inputs (i.e., spending on school fees and school-related materials such as books, uniforms, etc.) depends on household income. The decision to curb household human capital investment in response to negative income shocks may differ across children based on how the parents perceive the value of child labour and the return on their investment.

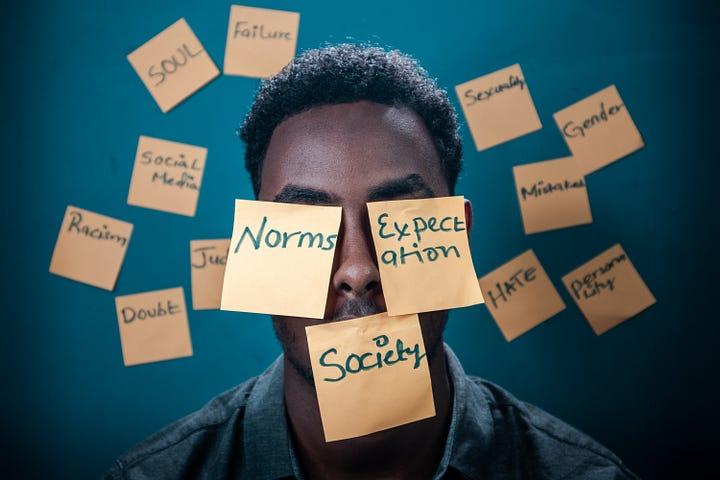

The Mediating Role of Gender Norms

Gender is an important sociocultural element that may mediate individual resource allocations within a household and, thus, may dictate who bears the burden of aggregate economic shocks among boys and girls. Societal gender roles have a substantial effect on shaping parents’ expectations of costs and returns on human capital investments within the household. While households in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) display a preference for variety (equal number of sons and daughters) or no preference at all when it comes to fertility patterns, this does not mean the absence of inequality when it comes to attitudes towards gender roles.

The origins of societal gender roles are linked to the form of livelihood activities practised in a society. Present-day societies that practice traditional plow agriculture have gender norms that persistently discriminate against women’s participation in workplaces, politics, and entrepreneurial activities. In these societies, the prevailing discriminatory gender norms give women subordinate status in the community. This may compel parents to perceive girls’ labour as having a lower rate of return and, consequently, prioritise boys when investing in human capital.

Of key interest here is that perceived returns, which influence child human capital investment decisions, are lower than actual returns in the Dominican Republic. Despite the lack of concrete empirical proof in the context of SSA where the majority of households are illiterate and less-informed, and the prevailing gender norms discriminate against women, it is highly likely that parents substantially underestimate the returns to their investment in human capital of female children. As such, households may underestimate the costs of gender bias and continue to assign lower values to female children’s education and their economic contributions to the household.

The livelihood of the majority households in SSA depends mainly on physically intensive productive activities rather than on mental tasks, disfavoring girl’s comparative advantage and unrecognising their contribution. In this context, when rural households experience negative income shocks, they may divert their human capital investment spending away from female children. In the eyes of parents, reducing their investment in human capital for girls is a lower opportunity cost of labour than reducing investments in boys. Consequently, during shock periods, female children receive lower household investments in terms of nutrition and use of medical services and are more likely to have poor health status. Ill health adversely affects schooling, hence, further widening the gender gap in education.

This has far-reaching repercussions because it generates a feminised poverty trap. Households in a society with discriminatory gender norms see less value in investing in the human capital of female children because the assumption is that women are only capable of handling low-value tasks inside the household. Ultimately, girls with low human capital become women with reduced earnings potential and low socioeconomic status, which limits their capacity to financially support their parents. This completes the vicious cycle, perpetuating parents’ gender bias by discouraging them from investing household resources in the human capital of girls. Therefore, where prevailing gender norms assume women’s roles are limited to unremunerated domestic and reproductive tasks, the income effect of aggregate economic shocks reinforces gender inequality because households feel compelled to invest less in a female child’s human capital.

Thus, laying out the interplay between household and social behaviour helps policymakers, development practitioners, academicians, and private businesses to understand why parents prioritise the health and physical well-being of boys, particularly in agrarian societies.

Is There a Way Forward?

In sum, in the face of aggregate economic shocks, preexisting gender biases cause household human capital investment decisions to be based on the sex of the child, typically to the detriment of girls. How to escape the perpetual cycle of girls being undervalued and disfavored when it comes to household investment in health and education? Seema Jayachandran (2015) posited that “the cultural institutions favouring males might themselves fade naturally with economic modernisation, enabling gender gaps to close,” but follows this up by pointing out “there is also scope for policymakers to expedite the process” (p. 84). An important place to start is with an empirical investigation on the effect of aggregate economic shocks on household investments in child human capital conditional on gender in the SSA context. This will have valuable policy implications, helping prioritise those disaster responses that intend to mitigate gender biases and, in turn, alleviate gender inequality in human capital development in SSA.

Includovate does a lot of work around these topics. Read more here.

About the author

Kaleab Kebede Haile is a development economist who works as a Principal Researcher at Includovate. His educational background includes a PhD in Economics and Governance from Maastricht University and a Master of Science in Agricultural Economics from Haramaya University. His fields of research interest and expertise include impact evaluation, gender analysis, climate resilience, lab and field experiments, adoption of agricultural technologies and innovations, food and nutrition security, human capital development, and poverty and inequality dynamics.

Includovate is a feminist research incubator that “walks the talk”. Includovate is an Australian social enterprise consisting of a consulting firm and research incubator that designs solutions for gender equality and social inclusion. Its mission is to incubate transformative and inclusive solutions for measuring, studying, and changing discriminatory norms that lead to poverty, inequality, and injustice. To know more about us at Includovate, follow our social media: @includovate, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram.